Does the National Endowment of the Arts Pay Divedends

The Heritage Foundation and conservative groups like it have been trying to kill the National Endowment for the Arts for decades.

Concluding month, the Trump administration, for the quaternary year in a row, released a upkeep blueprint that proposed zeroing out and winding downward the NEA and other authorities art support. Heritage basically staffed the electric current Trump administration , so information technology'due south not a coincidence that his budget priorities are essentially those of the anti-authorities think tank, which is about every bit passionate about catastrophe the NEA every bit information technology is near undermining the scientific discipline on climate change.

Perhaps with everything going on correct now, and with the NEA having squeaked by before, the sense of urgency around the issue has drained. You can't but go on writing passionate defenses of it year later yr. And then also, today'due south NEA itself, as even its critics acknowledge, is non exactly a behemoth of radical interventionist authorities to go inspired by.Nevertheless, information technology is worth defending.

The Heritage Foundation is still promoting its 1997 report authored by "distinguished swain" Laurence Jarvik, titled "Ten Good Reasons to Eliminate Funding for the National Endowment for the Arts," as the definitive source on " why at that place is no need for the federal government to be spending your money on these programs." I t remains a go-to reference in debates today, and its language has sunk into the basis water of conservative argument near the NEA—which is, after all, the job of a conservative think tank.

And actually, every bit a distillation of anti-NEA talking points, I find information technology useful. I think it'south important for NEA advocates to really sympathise the spectrum of arguments ranged against them, and not rely on dated or off-target counter-arguments. So I thought I would put down, here, replies to each of Heritage's "Ten Reasons."

Anti-NEA Talking Point #ane: The Arts Will Have More than Than Enough Back up Without the NEA

Reply: Defenders of the NEA often utilize the talking point that its funding accounts for a very, very pocket-size amount of the budget: something like 0.0004 pct. But foes can turn this around: What is paltry is piece of cake to cutting. Trump'south 2021 budget proposal says explicitly that the NEA and NEH "make upward merely a small fraction of the billions spent each year by arts and humanities nonprofit organizations."

But the NEA was never designed to replace private support. The very second particular of National Foundation on the Arts and the Humanities Act of 1965 states this clearly: "The encouragement and support of national progress and scholarship in the humanities and the arts, while primarily a thing for private and local initiative, are also appropriate matters of concern to the Federal Authorities."

Later signing a bill renaming the proposed National Cultural Center the John F. Kennedy Centre for the Performing Arts here at the White Business firm today, president Johnson hands 1 of the pens he used to senator Edward M. Kennedy. Photo courtesy Getty Images.

Instead the NEA was designed to assist correct for the biases of private support. It was hatched in 1964, the same year Dylan pennedThe Times They Are a Changin', and information technology was very much of a piece with the spirit of Johnson's Great Society. That is, the idea was that government action could exist used to correct some of the issues that, left to itself, the US'due south flush gild—then in the centre of a historic boom, but simmering with unrest—let fester.

The accent, every bit you lot can read in its showtime written report of 1964-65, was that the arts ought to be recognized "equally a vital part of our national life, and not a luxury." The initial commission that studied information technology had come to the conclusion that the relentless focus on applied subjects in didactics had led to widespread discontent with the materialism of US social club. It thus focused on expanding access to the arts and funding ideas and artworks accounted vital but not necessarily assisting.

Let's non be naïve well-nigh it: much like the Johnson Administration's eventual support of the Civil Rights Act, the passage of the NEA was besides meant as a chess move in the Common cold War. Capitalist America was in ideological competition with the Soviet Marriage for global hegemony, and trying to cutting confronting the paradigm of the US on the globe stage as a bigoted, rapaciously materialist gild served an objective. The human activity itself made its propaganda value clear: "The world leadership which has come to the The states cannot rest solely upon superior power, wealth, and technology, merely must be solidly founded upon worldwide respect and adoration for the Nation's high qualities as a leader in the realm of ideas and of the spirit."

Flashing forward, that groundwork impetus for government fine art funding helps explain why it was later on the Cold War ended in the belatedly '80s that the NEA came under withering assault, as U.s. politicians no longer felt the same ideological need to soften the prototype of capitalism to the earth; capitalism had become the only game in town. Since then, conservatives have either demonized or allow the NEA go to seed. In 1990, the NEA'due south budget was $171 million, which after inflation adds up to something like $338 million; for 2020, it's $162 million.

But the issues that it was set upwards to accost—the construal of art equally a "luxury" when left just to private patronage, and major gaps in access to creative resources in a wealthy but very unequal society—definitely remain. And through its modest grant-giving today, the NEA withal does what information technology was designed to practice: attempt to foster access to the arts for people of many different kinds, mainly through supporting non-profit institutions that can use the lift.

Anti-NEA Talking Point #2: The NEA Is Welfare for Cultural Elitists

Reply: The NEA was founded in the '60s with a rhetoric of promoting "progressive" and "experimental" art, and took oestrus afterwards for discriminating confronting realists. In the late '80s, it became a flashpoint of public controversy, with "artists" proving easy to demonize every bit godless deviants.

But honestly, all this is a very dated idea of what the NEA does. The NEA is quite cocky-consciously populist in focus these days. It boasts of promoting such initiatives as the Creative Forces program, a partnership with the U.S. Section of Defense and Veterans Diplomacy that, equally its website states, "increases access to customs arts activities to promote wellness, wellness, and quality of life for military machine service members, veterans, and their families and caregivers."

Colonel Michael Southward. Heimall, director of Walter Reed National Military Medical Centre; Rusty Noesner, Retired US Navy SEAL; Jane Chu, Chairman of the NEA; Captain Walt Greenhalgh, manager of the National Intrepid Middle of Excellence (NICoE); and commander Wendy Pettit, Chief of Clinical Operations, National Intrepid Center of Excellence (NICoE) hold upwardly masks made by service men and women in the Creative Forces plan. Prototype courtesy National Endowment for the Arts.

Last September, the Jacksonville Daily News reported on an Open Studio exhibition for Creative Forces, which gives a sense of the hoity-toity audience information technology serves. "Information technology'southward like a safe space for me; a place I can go and express myself," Ground forces vet Robert "Shrek" Harrell, an artist in the show, said of the Creative Forces program. "It gives me time to be with myself in my heed, and gives me some peace and a manner to heal."

The NEA also supports Claiming America, a programme specifically designed to give a helping hand to communities that might otherwise not have access to art programming—i.e., it is specifically targeted at non-elite communities.

Just as an instance, we are talking about a grant for North Carolina'south Tsali Care Heart to support artists from the Eastern Ring of Cherokee Indians to offer art classes to the nursing habitation's residents (who are also generally tribal members). Or a grant to support an art exhibition and other programming for a Dia de Los Muertos festival in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Or a grant for the Georgia Mountain Storytelling Festival in Blairsville, Georgia, which showcases "traditional and contemporary Appalachian stories."

All of these seem extremely worthy, and hard to frame as welfare for elitists.

I actually don't dear making such arguments, because I think that there ought to be room to fund fine art that isn't directly justified every bit community service.

But what I retrieve is very important to stress is that the NEA is modestly redistributive. Private philanthropy is notoriously diff, flowing to flashy showpiece institutions and pooling in localities where rich people are concentrated. The fine art market is even more than a direct reflection of the concentration of wealth, and wealth has never been more concentrated.

"Low-dollar and mid-level donors have declined by about 2 percent each year for more than fifteen years," one written report on trends in philanthropy found recently. The result was "an increased bias toward funding heavily major-donor-directed boutique organizations and projects." And and so you get the mega-project of the Shed in New York's luxury shopping playground Hudson Yards, with its flashy "Bloomberg Building," at the very moment that the insufficiently ultra-modest but love Bushwick nonprofit NURTUREart has to shut down due to a "confluence of resources challenges and a shifting environment for non-profits."

On this level, the statement for a National Endowment for the Arts is clearer now then it has e'er been. Compared to when the NEA was founded, the United States has grown drastically more spatially unequal, with certain large cities and regions sucking up investment and cultural amenities. Even experts who fence that the NEA should be even more than narrowly focused on small, not-elite institutions—I'grand thinking of Diane Ragsdale—stress that NEA funding tends to be more as distributed, since that's part of its mandate, and also come across information technology as a potential musical instrument for correcting for otherwise dire trends in private giving.

But don't have my word for it. Trump's NEA secretary, Mary Anne Carter, made the case well last year:

For every canton in America that has a high school, National Endowment for the Arts is at that place, either through our Poetry Out Loud competition or our Musical Theater Songwriting Challenge. The aforementioned cannot be said for private foundations. A review of the art giving of the top 1000, yes, chiliad private foundations shows that those private dollars don't reach 65% of American counties. In contrast, the National Endowment for the Arts is in 779 more counties than private foundations.

779 counties, 25% of America where the National Endowment for the Arts provides funding where the meridian thousand private foundations practise not.

A few examples: in Kentucky there are 59 counties that receive funding from u.s.a. that have no individual dollars out of 120 counties. In Alabama 40, in South Carolina 10, Alaska eight, and in my home state of Tennessee 21 counties with our funding just no funding from the acme grand individual foundations.

Admission to arts funding should not depend on i'southward proximity to private philanthropy. This is what makes support of the National Endowment for the Arts indispensable.

Anti-NEA Talking Point #iii: The NEA Discourages Charitable Gifts to the Arts

Answer: This is a chip of a wonky debate, but argument rages over whether regime funding of the arts "crowds out" or "crowds in" private funding. Supporters similar to say that the NEA serves equally a "Expert Housekeeping" seal, encouraging donations from individual foundations, corporations, and individuals, an effect that certainly feels truthful to a lot of small organizations who apply an NEA grant to attract the attention of other potential backers.

When the new effort at termination was announced last month, an NEA spokesperson told my colleague Eileen Kinsella that its grants "are leveraged past other public and private contributions up to ix:1, significantly increasing the affect of the federal investment." (Indeed, its grants generally require securing matching funds.)

Opponents such as the Heritage Foundation like to say that government support simply "crowds out" private funders, who will accept their money somewhere where they call up information technology is more than needed if the government is present. And any "Good Housekeeping" effect, they say, simply shifts patronage that would become to ane system to another organization, rather than encouraging additional giving.

I actually notice it baffling to try to eddy this down to a universal law. For example: private giving went up in the '90s subsequently the cuts to the NEA caused by the Culture Wars. Does that therefore show, every bit some economists have argued, that government arts funding had previously been "crowding out" private patronage?

I don't recollect so, considering a) the increase in private funding happened during a huge economic boom that lasted the entire decade, and b) the spectacular public grapheme of the Civilization Wars debates that led to the NEA cut framed it in the public mind as a needy cause worthy of supporting, with copious PR points and skilful vibes going to the private philanthropists who stepped in as Congress cut funding. (The manner the researchers put this, in their charmingly inscrutable style, is that "publicity" has a "not-linear touch on" on the public-private funding calculation.)

When an economic crisis hit in the early 2000s and progressive concern recentered around the Iraq War, the conversation moved on: "Data from the Conference Board for 2000 to 2010 propose that corporate funding for the arts dropped by half after inflation over this catamenia." And that'southward not really considering George W. Bush'southward NEA stepped back in to crowd it out. The NEA was still downward by a tertiary from its heights after inflation at decade's end.

A terminal note: Even if in that location is a stock-still pie of private arts funding, and the "bespeak" of an NEA grant only shifts those donations effectually, it does not follow that this cannot exist a useful operation. Larger, well-endowed institutions are easier able to court donors and to frame themselves as winners. The "Seal of Approval" from the NEA most benefits small institutions who don't otherwise have major marketing budgets or pre-existing networks of big donors to tap into, providing a way to bespeak, "Hey, this organization is doing adept work—might you consider shifting some money from that wealthy, well-established system to a smaller merely critically acclaimed one?"

Anti-NEA Talking Betoken #4: The NEA Lowers the Quality of American Art

Answer: Heritage quotes a direction professor on the evils of state arts funding: "Information technology was the unsubsidized writers, painters, and musicians—imprisoned in their homes if they were lucky, in asylums or in gulags if they weren't—who created lasting civilization."

Aside from being comically over the top ("giving $10,000 grants to pocket-sized nonprofits is the majestic road to totalitarianism!"), this declaration is on-its-face wrong, unless you don't count Velázquez or Bernini as "lasting civilisation." Most of the things y'all see in museums were subsidized by royal courts or papal authorities in one mode or some other.

Simply I value the modern "artist as dissident" effigy also. Does government art funding necessarily turn artists into mediocre propagandists?

The "New Deal produced no truthful masterpieces," Heritage reports, using the WPA arts projects as an obvious example of bad arts policy. But "producing masterpieces" isn't the all-time measure for an arts policy designed as unemployment relief in the first place, and arts policy in general doesn't just back up private artworks only helps artists sustain a career, become training, and experiment. Most serious scholars today argue that the New Bargain arts program laid the basis for a national arts scene in the United States that did not previously be, producing a new sense of professional identity and purpose for American art that paid dividends afterwards on.

Jackson Pollock, Alice Neel, and Charles White all cut their teeth equally WPA artists, and went on to keen renown in diverse means. You can't beat that record.

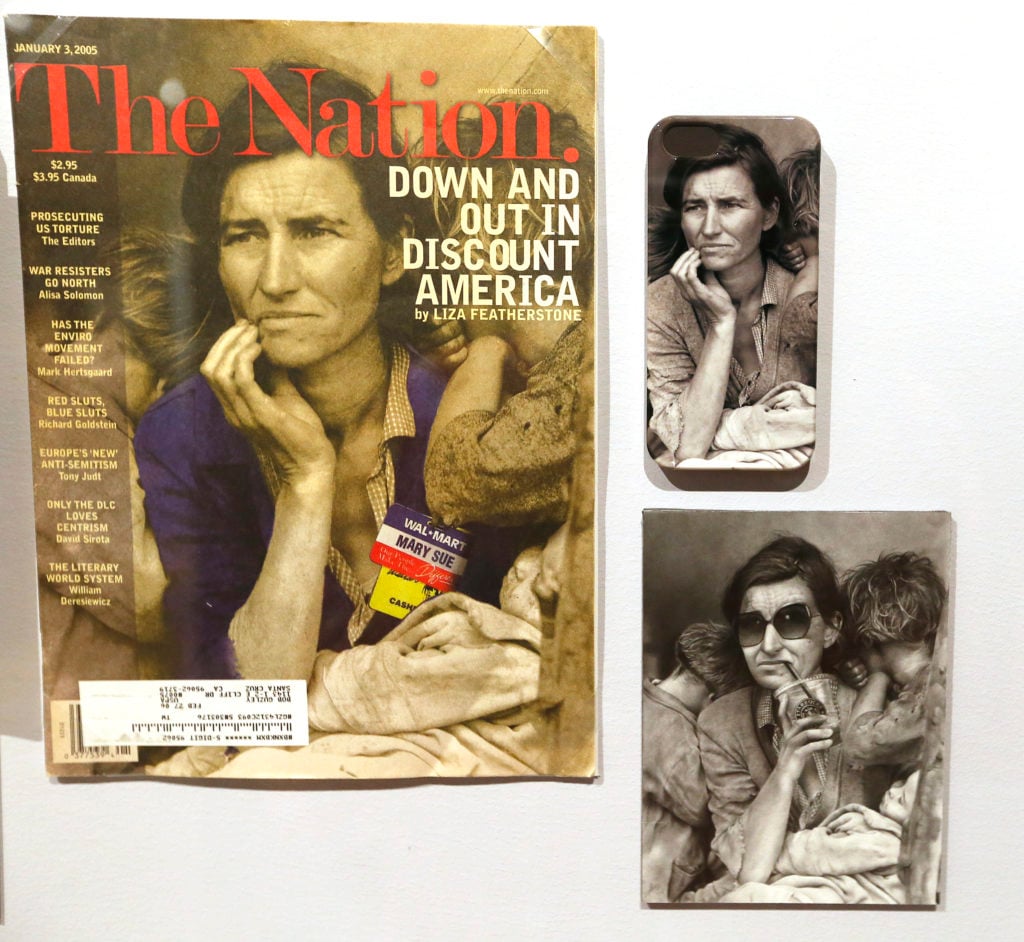

A magazine cover, jail cell phone case, and postcard with versions of Dorothea Lange's Migrant Female parent photograph are displayed during a media preview of the exhibition "Dorothea Lange: Politics of Seeing" at the Oakland Museum of California on Th, May 11, 2017. Photo by MediaNews Group/Bay Expanse News via Getty Images.

As for "masterpieces," I don't know what else to call a work that has entered every bit deeply into the symbolic vocabulary every bit Dorothea Lange'sMigrant Female parent, which was created for the Farm Services Administration'due south photography section.

The NEA, back when information technology still had private artist grants (these were a casualty of the Culture Wars fight in the '90s), did a pretty skillful job supporting artists who were in need at stages in their career when it mattered, and who went on to make important art. Michael Brenson looked at artists who won MacArthur "Genius" Grants just after receiving NEA grants starting time—which was almostall of them given during the relevant fourth dimension period where the ii programs overlapped: Ida Applebroog, Vija Celmins, Ann Hamilton, David Hammons, Gary Hill, Robert Irwin, Alfredo Jaar, Kerry James Marshall, Pepon Osorio, Martin Puryear, Cindy Sherman, James Turrell, Bill Viola, and Fred Wilson.

In many cases, Brenson points out, they received the NEA grant over a decade before they officially became celebrated every bit "Geniuses," and the heave helped them stick it out on what was and is a tough path. The fact that Kerry James Marshall, probably the most acclaimed and of import living painter today, was allowed to pursue his fine art full fourth dimension because of his 1991 NEA grant is part of his official biography.

And then you lot tin dispense with the "government funding leads only to mediocrity" line.

On the flip side, however, it may be worth adding that I find no bear witness that the alternatives to government funding don't produce their own biases, specially in the confront of full-bodied wealth, the plummet of the middle of the art market, and an increasingly inescapable corporate popular culture. The results of those pressures include the "Zombie Formalism" painting boom of a few years ago—where galleries were swamped with blandly gimmicky abstract paintings, courting herd gustation in collectors—or every museum badly trying to get a concur of a Yayoi Kusama mirror room to bring in the crowds.

The individual market produces its ain pressures: towards flattering rich people and rubber corporate ideas of what's going to courtroom mass-appeal profitability. The bespeak of arts funding, once more than, is to provide a modest counterweight against theseother pressures towards conformity.

Anti-NEA Talking Indicate #5: The NEA Will Go on to Fund Pornography

Respond: This one dates the Heritage article. The year afterward it was published, in '98, the Supreme Court upheld an advisory "decency standard" for NEA grants. In 2010, looking back 2 decades on from that decision, the National Coalition Against Censorship wrote:

[I]t appears the decency subpoena—coupled with the removal of individual artists grants—did not so much become a reason to censor specific work equally have a chilling effect on programming at recipient institutions. It also seems that the subpoena shifted the NEA's accent from supporting innovative original work to supporting art and art education that would non likely disturb mainstream standards and values.

I'm not aware of anything since that changes the calculation. And yet, the Culture Wars permanently fixed in the public mind the clan of the NEA with Andres Serrano's Piss Christ and Robert Mapplethorpe'south BDSM photos. It's role of why it is so easy still to score points bashing the agency on Trick News.

It's easy to signal out that the Heritage report was more concerned with cherrypicking individual instances of controversial art to whip up outrage confronting authorities subsidy overall than with accurately assessing what any of the art in question meant. Among the items that Heritage wants to offer—fifty-fifty today, evidently—as irredeemably offensive is the NEA's back up of the system Women Brand Movies. The scandal was that WMM helped distribute films that had lesbian themes.

Similarly, the written report cheerfullyclassed the fact that the NEA'southward literature program helped fund "The Gay 100," a historical assimilate of famous gays and lesbians, equally "pornographic."The libertarian flacks at Heritage were happy to court homophobia to push button their anti-authorities agenda. That probably seemed a practiced bet in the tardily '90s. It looks plainly like nasty opportunism now.

Reviewing today the study's appendix purporting to evidence the "regular pattern of support for indecency, repeated year after year," a lot of it fudges the nature of the NEA's support, and a lot more than burlesques the works in question very uncharitably, takes hostile reviews as proof positive of worthlessness, and shows ignorance of the field it claims to authoritatively opine on. It refers to William Pope 50. equally "William Fifty. Pope." It includes as government-funded "pornography" the scandal of MoMA showing Bruce Nauman neons that say "Shit and Die" and "Fuck and Dice," because MoMA showed them and received some NEA funding. The horror.

Visitors line up for the Bruce Nauman works during the 53rd International Art Exhibition on June 5, 2009 in Venice, Italy. Photo by Massimo Di Nonno/Getty Images.

In the end, though, getting sucked into defending individual works is a waste product. Not anybody is going to be convinced to like Bruce Nauman. I mean, he did actually represent the The states of America at the Venice Biennale, where his acerbic, difficult piece of work won the Golden Lion for Best National Pavilion in 2009—something like winning a gilt medal in the Olympics of Fine art—but it is challenging for many viewers.

Debating the claim and demerits of private works of fine art, and even whether they wereindividually worth funding? That'southward a chore for criticism.

Outside of that, what you take to defend is the principle of the thing.

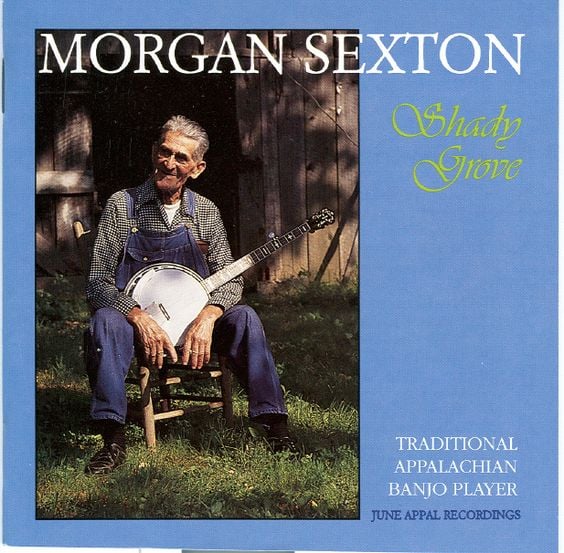

In 1989, the year of the NEA supernova of controversy, panelists gave out thousands of grants (298 in the before longhoped-for-terminated creative person-grants category alone!). These included funding such decidedly non-pornographic fare as a documentary almost banjo legend Morgan Sexton and a "radio series about women in old-time music" in Kentucky.

"Shady Grove" by Morgan Sexton, a 1991 NEA National Heritage Swain.

The NEA could avowal, that twelvemonth, of having funded the initial workshops that became the playDriving Miss Daisy, nominated in motion picture grade for Best Pic in 1990. It gave early back up to A Prairie Home Companion in the '70s. In the 2010s, Lin-Manuel Miranda workshopped his commencement musical at the O'Neill Musical Theatre Center, partly funded by the NEA.

Taking a few examples of things that the NEA straight or, more oft, indirectly funded that offended conservative sensibilities, and caricaturing government art fundingas a whole equally being a scheme to decadent the youth? That'due south textbook demagoguery.

Anti-NEA Talking Indicate #6: The NEA Promotes Politically Correct Art

Answer: There are interesting debates on this score. Governmental arts-funding systems are inherently subject to political pressures. That does tend to put pressure on artists to make work that avoids controversy. This is, bluntly, a complaint that some artists accept about more than social democratic arts-funding systems—though they usually wouldn't give them up, either. The International Federation of Arts Councils and Civilisation Agencies has some very idea-provoking give-and-take well-nigh what mix of "arm's length" policies all-time guarantee security and liberty for the arts.

Equally nosotros have seen, a lot of the NEA'southward intensified focus on "customs-focused" arts came in the wake of the Culture Wars. So if what you mean by "politically correct" is safe, advisedly workshopped, offends-no-one expression, you lot might exist able to make a case that the agency does somewhat tend towards this kind of work. But it is precisely the right's relentless efforts to demonize the NEA that have led to such "political correctness."

But that is not what Heritage meant past "politically correct" fine art. It meant that the "radical virus of multiculturalism" has "permanently infected the agency, causing creative efforts to be evaluated by race, ethnicity, and sexual orientation instead of creative merit."

Yet the 1 big slice of evidence Heritage mustered was an commodity by ane-timeLos Angeles Times theater critic Jan Breslauer in the Washington Post decrying how "race-based politics" had entered arts funding. Information technology's worth, and then, reading the volley of letters that the Post received rebutting Breslauer. Calling it "a crazy quilt of misinformation," Olive Mosier from the NEA wrote: "[Breslauer's] proffer that artists of colour have been presented more for their race or ethnicity than for their artistic excellence is demeaning and untrue. The isolated examples of those who contort themselves to qualify for a grant are the exception, and certainly not part of whatever rule hither at the National Endowment for the Arts."

What is true is that, as already mentioned, arts funding has been a pocket-sized manner to offer support for underserved communities: poor communities, minority communities, rural communities, disabled communities, veteran communities. Guaranteeing admission to the arts for a wide spectrum of the citizenry is part of what the NEA was designed to do: "The arts and the humanities vest to all the people of the United States," is the first line of its founding human activity. But saying that it takes those factors into consideration is rather different than proverb that it is placing "political definiteness" over "creative merit."

The idea that there is some easily accessed universal standard of "merit" to gauge art by is false. Cultural background matters a lot in terms of what is considered good. The factors that make a great dabble thespian and a great violinist are a petty unlike. The NEA funds both.

Here is what Michael Kahn, the legendary artistic director of the Shakespeare Theater, wrote the Mail service in response to the Breslauer essay that Heritage touts:

Such policies do not issue in 'pigeonholing artists and pressuring them to produce work that satisfies a politically right agenda,' as Breslauer maintains. Rather, such policies provide in a minor measure the means through which these artists may flourish and abound. By encouraging this dialogue, the NEA has created artistic possibilities in an environment that had previously not been hospitable.

Merely and so.

Anti-NEA Talking Signal #7: The NEA Wastes Resources

Reply: Heritage writes that, "[50]ike whatever federal hierarchy, the NEA wastes tax dollars on administrative overhead and bureaucracy." This is stated as a universal constabulary.

But there is no universal police that makes this "individual = proficient, public = bad" calculation axiomatically true. In health care, for case, government programs similar Canada's spend far, far, far less on administration than we practice in the United States, where our welter of private insurance companies compete to spend on advertising, marketing, administration, executive salaries, and shareholder profits. Merely 17 percent of Canada's health expenditures become to administration; 34 per centum of US health expenditures go to such things.

When it comes to the arts—and arts advocates should know the following fact, so that they can discuss it honestly—nosotros are always talking about a battle over how the authorities gives away money to back up the arts, non whether it does.

Our authorities gives away astronomically more money in tax breaks than it does in direct grants of money to the arts. The tax pause for charitable giving is the single largest style that the The states regime gives to the arts—orders of magnitude more of import than the NEA.

If your objection to arts funding is that it's wasteful to spend taxation money on arts, the NEA is just an incredibly small, random fight to option, while the revenue enhancement-interruption model ways that, essentially, authorities is subsidizing the social agenda of the wealthy, who get to write off their gala tickets and charity-auction purchases.

This model, of course, seems like a good deal from some angles: It incentivizes rich people to give to causes by allowing them to become the social and PR boost for doing so, while at the same time making sure the government isn't on the hook for the whole nib, since donors can simply write off part of their contribution. (Trump'southward 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act tipped the benefits of charitable giving even more towards the top.)

In an age when, for decades all over the world, the rest of ability has shifted away from the state and towards the wealthy and corporations, this has appeared to exist a skillful deal. We may admire governments similar Germany for their strong public arts support, just Europeans have been talking of the need to move towards "United states of america-manner" arts funding for some time.

In that location is, however, a nighttime side to this system. Or multiple dark sides.

For 1, it skews the priorities of institutions towards brusque-term thinking. It has led The states arts institutions to overbuild, for instance, as it is very hard to get private patrons to fund boring things similar operations and maintenance, because what donors desire are flashy new buildings and other highly visible initiatives to put their proper noun on, which lead to the most prestige. But to go on up in the race to court donors, an arts system and then heavily dependent on private giving is stuck in permanent expansion manner.

For two, cultivating patronage is non without its own wasteful administration costs. Rich people don't just give—they need to be romanced. In the '90s, for every new dollar of private giving raised, institutions incurred 25 cents more of fundraising costs.

Grant writing, of course, has its costs too: an often-cited effigy puts it at about 20 cents for every dollar raised. The preferred special issue/do good model, on the other hand, is thoroughly the most wasteful way to raise money for nonprofits, with an average of 50 cents spent for every dollar raised (and plenty of events that yield very little after the lavish amenities to lure the patron class are paid for, while sucking upward vast amounts of staff resources.)

The most toll-effective style to go coin is "major gifts"—but, to echo something that has been a theme here—information technology is the glamorous, established, most-connected major institutions that are best positioned to attract major gifts. Government arts funding is certainly not "wasteful" if information technology is viewed every bit helping to correct for this imbalance.

Protestors at the Guggenheim Museum stage a "dice-in" to protest Sackler funding. Photograph: Caroline Goldstein.

Finally, it'south worth noting that an arts system that tips things so far towards private revenue enhancement breaks has fabricated Usa institutions always more dependent on currying favor with the rich—which has now left them in a terrible demark, and the target of agitation, as exposure of corporate misdoings throws a harsher and harsher light upon the patron grade. Simply as dependence on government makes institutions vulnerable to anti-authorities movements, dependence on the mega-rich makes institutions vulnerable to pop protestation—and our country has grown and so skewed by its farthermost levels of inequality that it is cracking apart.

Anti-NEA Talking Point #eight: The NEA Is Beyond Reform

Respond: The only reason to believe this is if you dogmatically believe that, by its nature, the NEA is bad.

Information technology has reinvented itself over the years in many ways, partnered with new organizations, and created new categories of funding. In the recent past, these accept included its Our Boondocks grants (established 2010) for "creative placemaking," which is substantially arts funding targeted at local economical evolution, and the Blue Stars Museums programme (also established 2010), which makes museums free to active duty military machine and their families.

Outside a pop-upwards gallery in Mount Ranier, Maryland, an outcome in the Fine art Lives Here series, a recipient of an NEA Our Town grant. Photo courtesy of Fine art Lives Here.

There are debates about what the best forms regime arts funding might accept, definitely. You can argue over how it divides up its funds between larger and smaller institutions. You lot can lament the loss of the individual artist grants. You can doubtable that the "creative placemaking" doctrine amounts to substituting a weak arts policy for a strong regional economic development policy.

But, to me, the fact that foes of the NEA tend to be more interested in debatingwhether information technology should exist rather than debatingwhat it should do seems to suggest that opposition to it is actually about something else entirely… I wonder what that could be?

Anti-NEA Talking Point #9: Abolishing the NEA Will Prove to the American Public That Congress Is Willing to Eliminate Wasteful Spending

Reply: This is that "something else."

The volition to cutting the NEA has very little to do with the tiny NEA itself. It is symbolic. Information technology has everything to do with government arts funding as a symbol of the government doing things—something opposed ideologically by Heritage, not because what the NEA does itself actually is provably bad or particularly unpopular, but because bourgeois think tanks simply define government spending equally wasteful, a priori, and fine art funding seems an easy symbol of this waste matter.

Anti-NEA Talking Point #10: Funding the NEA Disturbs the U.Due south. Tradition of Limited Government

Reply: Hither's the last thing I volition say: The NEA is not even my preferred arts policy.

My preferred "arts policy" actually looks merely similar practiced social policy. Information technology looks like robustly funding public education, including arts programs for all students—subjects that have been cut in general, even as affluent parents keep them for their own kids. This kind of public funding cultivates a futurity audition for arts, proves the social benefit of the arts, and, of course, provides jobs for artists that utilise their talents.

It would look like a housing program and an end to turning cities into luxury playgrounds for concentrated wealth. Having a inexpensive place to piece of work and an affordable place to alive are what make art scenes thrive.

Information technology would look similar a robust social safety net, to provide the kinds of defenses against extreme precariousness that make it easier to sustain a creative practice if you don't happen to be born into a fortune.

In comparison to all these things, the NEA is an example of express government intervention. Merely I'm in favor of it, I'm in favor of expanding information technology, and I'm in favor of defending it as a symbol of a much broader principle: non giving in to the austerity-for-the-many, worship-of-unchecked-capitalism mindset that institutions like Heritage continue to push button, year after twelvemonth.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay alee of the fine art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the chat forwards.

Source: https://news.artnet.com/art-world/10-practical-reasons-need-fund-defend-national-endowment-arts-1789539

0 Response to "Does the National Endowment of the Arts Pay Divedends"

Post a Comment